Pawnee Writings

Contents:

The First Pawnee Writers

Pawnee Christmas Stories of Long Ago

A Pawnee Poetry Salon

*******

Visit Pawneeland

*******

The First Pawnee Writers

February 2009

During the 1980s I got interested in finding things written by Pawnees. One day I came across a convenient and excellent resource that helped me look for Pawnees who had published writings long ago. This was a book by Daniel Littlefield and James Parins: A Biobibliography of Native American Writers, 1772-1924 (1981), together with A Supplement (1985).

In early 1988 I studied these two books closely and prepared a list of all the Pawnee writers. With this list in hand I went up to the library at the University of Colorado and I had them order copies of those old publications via interlibrary loan. Slowly responses appeared.

I didn’t get everything I wanted. There were items that Littlefield and Parins had found that the CU librarians couldn’t locate for me. And there were some things I didn’t feel very interested in at the time, like this entry by Littlefield and Parins: “Fields, Arthur (Pawnee): ‘Calisthenics,’ Bacone Chief, Bacone College, 1924, p. 128.” I hadn’t done very well in school with calisthenics and I had graduated from high school with a rather skinny physique, and I still didn’t feel very interested in calisthenics in 1988.

Over twenty years later, gathering up all the things I did collect, I found it interesting to read those old publications, to get a sense for the cultural world inhabited by those Pawnee writers of the early 20th century. A few cultural circumstances are prominent in these writings, such as Americanization, Christianity, racialization, and pride in Pawnee identity.

Today it’s common enough to find Pawnees thinking and writing very analytically about 20th century Americanization, about religious issues, and about being Pawnee. Doing race as Pawnee Indians, it seems to me, is still done today pretty much the same way as the Pawnees of the early 1900s did it. Some aspects of American racialism have changed, of course.

In any case, it’s interesting to glimpse the vanished experiences of those Pawnees who lived in the world of early 20th century America. The works that appear below were prepared by Pawnee boarding school students and former students. From 1902 to 1916, these little writings appeared in various school publications. Presenting the stories, I begin each one with a brief note about the author.

*******

- November 1902 Letter by Louis Bayhylle

- The Indian Story By Henry Roberts

- The Horse and the Buffalo by Elmer Echo Hawk

- Abraham Lincoln by Simon Fancy Eagle

- The Buffalo Chase by Clifford Taylor

- Four Arbor Days by Clifford Taylor

- My Trip to Eagle’s Mere by Lucy West

- Powhohatawa by Samuel Osborne

- Pawnee Signs and Fable by Henry Murie

*******

Pawnee Christmas Stories of Long Ago

November 2003

When did Pawnees begin celebrating Christmas and what did this observance look like? Pawnee lifeways saw great changes between 1870 and 1930, when Pawnees became Americans, and this is reflected in the changing character of public ceremonial events, both religious and civic. By the end of the 19th century, Christmas had found its way into the lives of the Pawnee people.

The use of evergreen trees in American Christmas practices extends back to the 19th century. As Pawnees encountered Christmas customs among the Americans throughout the century, they must have noted the special use of evergreen trees. This echoed Pawnee religious practices, which placed special significance on cedar trees.

In the early 20th century, in fact, Pawnee Bear Dance ceremonialism involved a cedar tree laden with gifts that were distributed at the end of the ceremony, as described in James R. Murie’s Ceremonies of the Pawnee (p. 341-342). In this ceremony a special cedar tree was selected and ritually cut down for placement in the Bear Society earthlodge. In the course of moving the tree, women competed to place gifts with the tree, and all but four of these gifts were later distributed among the Bear dancers. This tree was kept in the ceremonial lodge for several months and then ritually retired with its gifts.

By this time, the Pawnees were celebrating Christmas as a communal holiday, gathering for several days in a “Christmas camp.” The activities superficially resembled Bear Society practices in the use of a tree, but this event represented an adaptation of American holiday customs. The Pawnees and Americans were exploring meaningful forms of cultural interfaces and Christmas provided one opportunity for this process.

Christian ideas influenced this new holiday, but Pawnees did not have to be practicing Christians to participate in Christmas doings. It was a communal event rather than a family holiday. Even so, by the 1890s, most Pawnees were experimenting with various forms of Christianity, primarily through Ghost Dance and peyote religious practices. Growing numbers of younger Pawnees were also becoming active in Protestant Christian churches, and in the early 1920s one observer estimated that “about one-fourth of the Pawnees...are members of some Christian church” (The Indian Leader, volume XXVI, number 30, April 20, 1923, quoting from an article by Leo E. Liegerot, “The Effect of the Oil Industry on the Oklahoma Indian,” Tide Water Topics, September and October issues).

The four accounts presented below preserve a very special historical record of early 20th century Pawnee Christmas customs. The first and earliest account is by Lucy Little Chief, a Kitkahahki and a granddaughter of Crazy Horse (who was a brother of my great-great-grandfather). Lucy was age 14 or 15 when she wrote the story in 1907, and she died two years later on February 12, 1909. Of the other three authors, Jennie Pratt was also Kitkahahki, and Vivian Roberts and Herman Ricketts were both Skidi. They were probably in their mid-teens when they wrote their stories in 1922.

All four were students at Haskell Institute, and all had grown up with Christmas as an annual Pawnee-American community holiday. Their writings are obscure but important, and they deserve to be remembered and appreciated today as some of the earliest Pawnees writing in English.

*******

- How Pawnees Celebrate Christmas by Lucy Little Chief

- A Christmas Story by Vivian Roberts

- An Indian Christmas Story by Jennie Pratt

- An Indian Christmas Celebration by Herman Ricketts

A Pawnee Poetry Salon

March 2009

Lyric poetry in the form of songs must certainly represent an ancient art-form among the Pawnee people. And during the late 19th century or early 20th century, as Pawnees learned the English language and attended boarding school, Pawnees also began to write lyric poetry in English.

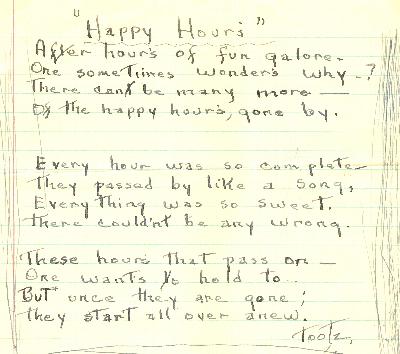

But to my knowledge, the earliest Pawnee who took up the writing of poetry in English was my grandmother, Lucille “Tootz” Echo Hawk. Born June 5, 1907, she was the daughter of an Otoe, Richard Shunatona, and a Skidi Pawnee, Jennie Bayhylle.

Tootz married George Echo Hawk (a Kitkahahki Pawnee) in late 1927, and the next year prospectors struck oil on a piece of land inherited by George. Suddenly wealthy, George bought some property west of Pawnee, Oklahoma and built a modest mansion. This became the Echo Hawk family home known first as the “Lazy E Ranch” and then as “Out West.” Between 1928 and 1933 Tootz bore four children with George, including my father (their oldest son).

Tootz also slipped into poor health due to a heart condition, and the family moved to New Mexico, hoping this would prove beneficial for her. The family dwelt in Albuquerque on South Harvard from the mid-1930s to 1939.

The Echo Hawks resumed residence Out West in 1939. Tootz’s health continued to decline, and she spent much time in Tulsa, staying with her brother, Joe Shunatona. In the years after World War II, she became bed-ridden. Lucille Echo Hawk died in October 1948.

Transcribing ten of Tootz’s poems for this project, I have organized them according to their likely chronological sequence. Her manuscripts lack dates – the earliest clearly datable poem is “Today I am Thirty,” written June 5, 1937. Several poems that concern her young children probably originated during the late 1930s, and a few others can be dated from internal clues.

“The Cactus” summons up the New Mexico landscape and bears a note on the back which refers to her daughter, born in August 1933: “Georgette Kindergarten Recital Jan 27th Friday nite.” This note appeared in January 1939, so the poem on the obverse was written before that date. Another poem, “Two Friends,” mentions Henry and Ruth Matrow, as “wed twenty years.” Henry was born about 1890 and Ruth was born about 1901, suggesting this poem was composed around 1940. Finally, in early 1948 Tootz wrote an untitled poem mentioning the marriage of her oldest son, Walter, to my mother, Jeanine.

In March 2009 my mother recalled hearing Tootz read her poetry during the 1940s. She said Tootz organized a women’s poetry salon that met occasionally Out West. Tootz paid my mother’s sister, Ruth Helen, to play unobtrusive background music for these poetry gatherings. Ruth Helen played her accordion while sitting in the nearby bathroom.

Pausing here & there in her life in Albuquerque to experiment with poetry, after returning to Oklahoma, Tootz decided to organize a social group to share this interest. They listened to music, read verses, and talked about local doings and events in the wider world beyond. Perhaps as a means of sharing some of her favorite poems with these friends, Tootz’s papers include transcribed works by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Walt Whitman, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and several other poets.

After Tootz died, George Echo Hawk kept a sheaf of her handwritten and typed poems. After his death in 1962, these papers ended up with his youngest son, Myron “Hobe” Echo Hawk. Myron placed these manuscripts into my keeping during the late 1980s.

Among these papers is a handwritten composition on education in which Tootz observed that “Simple language is the most beautiful.” Her poems reflect this aesthetic sensibility, expressing the everyday introspections of a Pawnee woman who treasured family and friends, and who valued the warm fellowship of poetry.

*******

*******